Conflict in the workplace is inevitable.

Many see it as a problem, but managed in the right way, it can be leveraged to make your organisation and culture stronger.

A famous mediator, Ken Cloke, said "conflict occurs at the crossroads of a problem that needs to be solved and the skills that parties have or don’t have to manage that conversation".

Conflict situations become particularly stressful when you do not know how to deal with them.

If you try to ignore them or shift them (such as by allowing one colleague to temporarily work from home), they will inevitably erupt later, causing more harm.

In the current tight labour market, we are seeing conflicts being mishandled more and more as managers are promoted internally or hired from a small pool of applicants, without the necessary skillset or mindset to lead people.

When there is war for talent in the marketplace and the cost of living is skyrocketing, retaining people is hard.

Existing staff can start grumbling that they will find another job if you do not give them a promotion and raise.

If they have very good technical skills and/or they are likeable, this seems to be a reasonable course of action.

However, not all experts or "good sticks" make effective leaders.

When a person is an expert in their sector, they may not be aware that they are an amateur in other areas that are required for them to be successful in management.

For example, they may push their team to work in the same way they do or micro-manage them because they believe they are best placed to show their team how to do their job. This approach can be demotivating and create a culture that some might call "bullying".

Managers like this often suffer from "the Dunning-Kruger effect"; they mistake their own ability and intelligence to be better than those around them. They have a bias of illusory superiority so they cannot see their own incompetence.

As Jack Kelly at Forbes magazine put it in a 2022 article on this topic: "Basically, the person is too dumb to realise that they are stupid."

My reframe is that they are not unintelligent; they are simply not self-aware.

This effect can affect us all at times — the more we learn, the more we realise we don’t know.

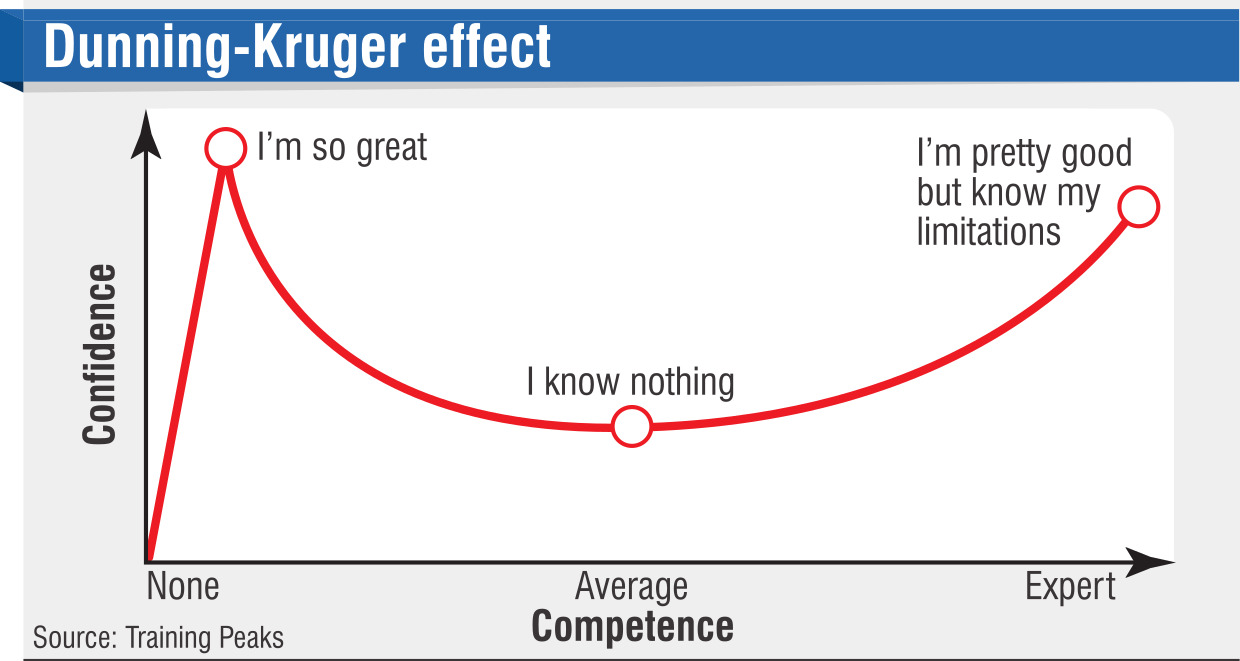

SOURCE: TRAINING PEAKS

The above diagram shows:

— When we know nothing, we can be too confident.

— When we grow to intermediate level, we think we know nothing.

— When we become an expert, we see our competence but we are aware of our limitations (and this is where "imposter syndrome" can take hold).

Now look at the graph displaying the Dunning-Kruger Effect. Notice the high confidence for the person with low competence.

Managers suffering from "imposter syndrome" do the opposite — they underestimate their abilities. They are often anxious and try too hard to manage because they do not feel they deserve their position.

People like this are likely to be perfectionists and will continually strive to better themselves.

While these attributes may make them seem like ideal employees, it can hinder their ability to lead.

They can often let their insecurities flow on to their team members and impose unnecessarily high standards and long working hours.

As they see themselves as experts, people who are under the Dunning-Kruger effect can be overly sensitive or dismissive when it is suggested that they need training in what they see as "soft skills", like conflict management.

They may blame other people or the working environment for what is really caused by their inability to manage their team well.

Even if they agree to do training, they can be challenging to train because they cannot see where they are lacking.

First, you need to create an environment where it is perfectly acceptable to learn and improve; in fact it is essential to innovation and the advancement of your organisation.

Next, you need to help them see their own knowledge gap.

One way of doing this to give them a project in which they have to apply skills you know they do not have — perhaps involving team members who are known to have the odd disagreement.

Keep a close eye on their progress and when it becomes evident a problem is developing due to their lack of skills (say, the arguing is detracting from productivity), ask them to report to you on how they think the project is going. If they do not make the connection, then you have the opportunity to make it for them.

Another option is to have them, their boss, their peers, and their team evaluate their performance as a leader in a 360-degree review.

This way they can compare how their team and peers sees them against their own self-evaluation.

It gives a full perspective from a number of different sources and levels within the organisation.

Once the penny has dropped:

— Get them personalised training over a sustained period. Make sure they have opportunities to put what they learn into practice.

— Let them know what great performance looks like. Perhaps assign them a mentor.

— Help them track progress with regular feedback. You may include this upskilling in their career development plan.

Once they become aware, there are things they can do to improve themselves as well:

— Learn to reflect on how they could have done things differently.

— Take feedback as an opportunity for professional growth.

— Be curious about why their colleagues see things differently and value those differences.

These tips should be supported by the development of a learning, open and trusting culture within your organisation as a whole.

For tips on how to fight imposter syndrome, please refer to Sarah Cross’ Connections column published on June 29, 2020.

Together we will continue to bring you more tips on how to make your organisations and people well connected this year.

This was published as an article in the Otago Daily Times on 30 January 2023.